A New Study Ties Anti-Bullying Laws to a Reduction in Suicide — but Boys Were Mostly Unaffected

Worrying reports of increased depression and anxiety among K-12 students, coupled with rising rates of teen suicide, have manifested the fears of American parents over the past decade. As the media draws greater attention to tragic cases of young people driven to despair at school, both doctors and teachers point to the perennial scourge of bullying as a culprit.

But new research finds some grounds for hope. According to a working paper circulated by the National Bureau of Economic Research, the nationwide spread of anti-bullying laws is associated with reduced bullying, depression and suicidal ideation among children between the ages of 14 and 18. The laws, perhaps the most prominent tool used by states to curb abusive behavior in school, also significantly decreased suicide in teen girls, the study finds.

Meaningful improvements in adolescent mental health will be greeted as a cause for celebration by lawmakers, who have enacted the statutes in every state and the District of Columbia over the past 20 years. But the study also finds that their beneficial effects are concentrated predominantly among young women, with male students seeing no decreased risk of suicide.

The study, conducted by economics professors Daniel Rees of the University of Colorado Denver and Joseph Sabia of San Diego State University, calculates the impact of anti-bullying laws on incidences of bullying, student welfare and suicide rates. To determine the effects, the authors relied on data from two sources: mortality information, collected by the National Vital Statistics System, and Youth Risk Behavior Surveys, coordinated by the Centers for Disease Control and administered by state and local health agencies.

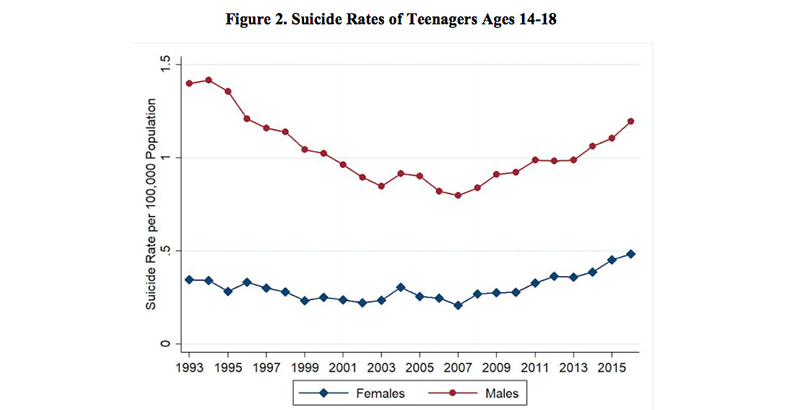

The administrative data show that rates of suicide and suicidal ideation have fluctuated significantly in recent decades. A lengthy decrease was observed between the early 1990s, when 29 percent of high schoolers said they thought seriously about killing themselves in the previous year, and 2009, when just 14 percent did. Over the past decade, however, that measure has again crept up to 17 percent. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration has also reported an uptick in the portion of children suffering major depressive episodes.

At the same time, the incidence of suicides increased by 56 percent among those between the ages of 10 and 24, surpassing homicide to become the second-leading cause of death within that age range. Importantly, suicidal behavior seems to differ based on sex: While studies have shown that girls are more likely to experience depression and make suicide attempts, teen boys are nearly three times as likely to kill themselves as their female classmates are. (This is, in part, a reflection of the long-documented “gender paradox” in suicide: Males of all ages end their lives at higher rates than women, though they report lower rates of depression.)

The triggers for these ghastly trends are still unclear, though psychologists have postulated a range of possible causes, from puberty-related hormone shifts to the rise of social media. One common response from states has been to adopt statutes compelling school districts to document and counteract bullying. Since 2001, every state has done so, but early returns have been mixed. One study indicated that kids enrolled in schools with anti-bullying initiatives are actually more likely to be victimized, while some have wondered whether discouraging abuse and harassment on school grounds would only push it elsewhere — perhaps to social networks online, which encompass more and more of teens’ social lives, and where adults have little power to shape behavior.

Rees and Sabia’s study offers compelling evidence that those worries are unfounded, and that students — particularly those from historically marginalized groups — see clear mental health benefits after their states implement anti-bullying legislation.

“We find that [anti-bullying laws] are associated with reductions in bullying victimization, depression and suicidal behaviors among high school students, especially among female high school students,” they write. “These effects appear to be largest — and extend to the most serious suicidal behaviors, including planning how to commit suicide and attempting suicide — for members of historically marginalized groups such as non-white female students and those who identify as LGBQ [Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and/or Questioning].”

To unravel the effects of these policies, the authors studied state-by-state mortality information and student behavioral surveys from before and after the laws’ implementation, controlling for such educational factors as student-to-teacher ratios, median teacher salaries, socioeconomic characteristics and local unemployment rates.

Girls, clearly, derive the greatest advantages. The adoption of an anti-bullying law is associated with a 5 percent drop in depression, as well as a 9 percent drop in suicidal ideation, for female students; male students saw smaller reductions in these phenomena that were not statistically significant. Those figures were even more pronounced for groups of students who are particularly likely to be bullied: Female LGBQ students were 21 percent less likely to be bullied at school given the presence of an anti-bullying law, and 18 percent less likely to plan to commit suicide.

Best of all, the worst and rarest form of self-harm — suicides — decreased by 15 percent for girls between the ages of 14 and 18. Unfortunately, no evidence was found of a concurrent reduction for boys.

Rees and Sabia offer no concrete explanation for the divergence in effects, though evidence suggests that adolescent girls are more likely to be bullied than boys. According to the National Center for Education Statistics, girls ages 12 to 18 are more likely to complain of being the subject of rumors, being insulted or being excluded. Earlier studies have shown that bullied girls are more likely to report anxiety and other health problems than bullied boys.

“One explanation may be that bullying generates more psychological trauma for female students and, as a consequence, the bullying being deterred by ABLs [anti-bullying laws] generates larger mental health benefits. Another potential explanation is that ABLs create safe environments in which students are more comfortable seeking social support and expressing their emotions, activities that may deter suicides and that are disproportionately engaged in by women,” the authors conclude.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)