Cleveland Sticks With Recovery Plans After Worst-in-Nation NAEP Drop

Scores are “startling,” but district is banking on efforts already in place or in the works

Help fund stories like this. Donate now!

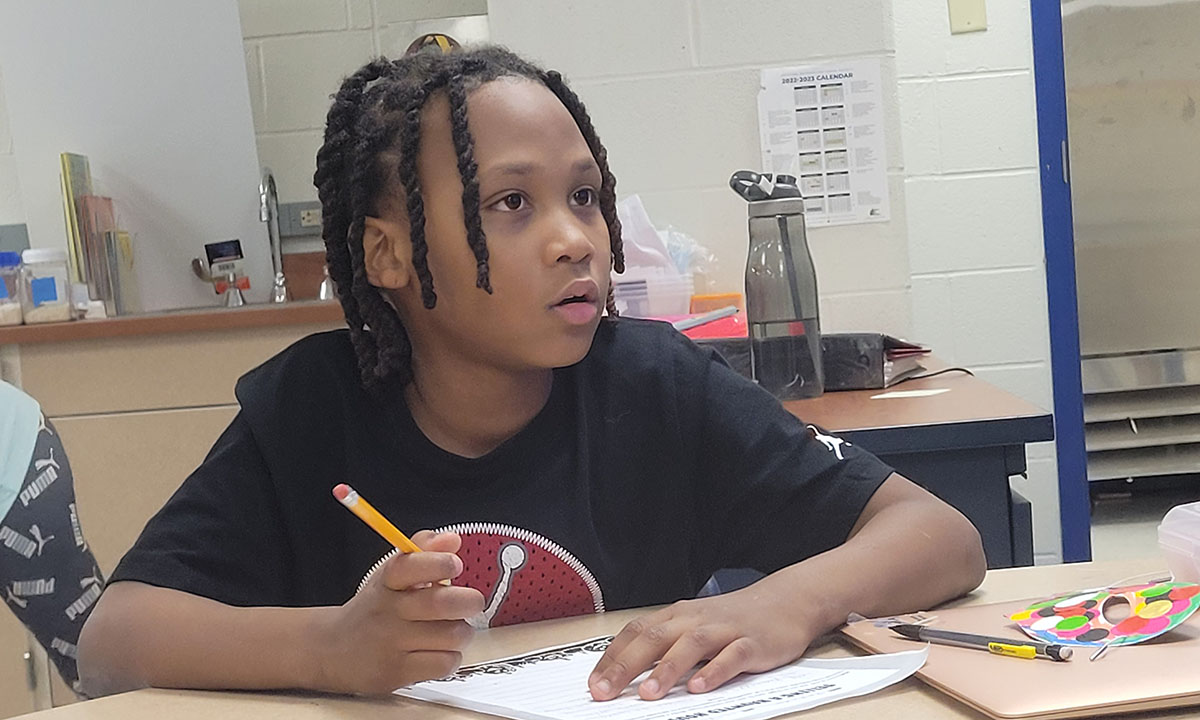

A chainsaw-wielding villain lurking in the haunted house spelled trouble for Cleveland third grader Jay’Ceon Burton.

Thankfully, teacher Tawana Dukes was right there for the rescue.

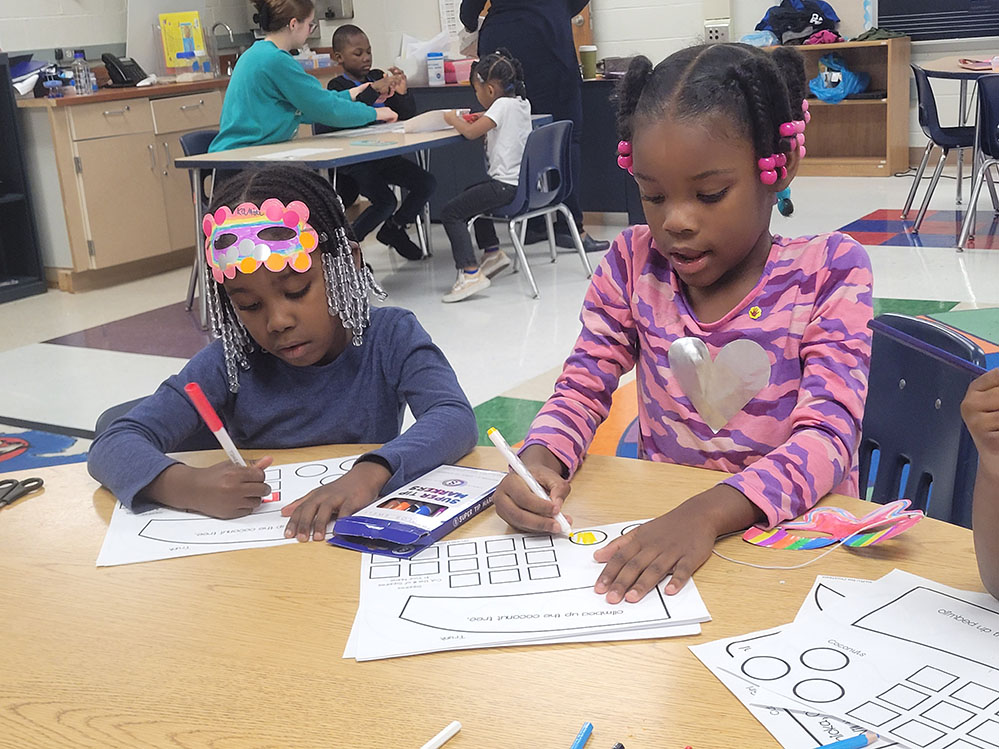

Jay’Ceon and his classmates at Mary B. Martin Elementary School in Cleveland had a fun afterschool task as they wound down from Halloween earlier this month: Describe a haunted house. Jay’Ceon had many ideas — including some popular movie characters along with the chainsaw maniac — but needed a hand putting them on paper.

“Sound it out,” Dukes told him, as he started writing, turning the task into a real lesson. “Chain..Saw. Compound word. What makes a ch sound?”

The stakes of the exercise were clearly not the same as dodging a real chainsaw. But for students at Mary Martin and all of the Cleveland school district, the stakes are still high.

Cleveland students’ ability to read was devastated by the COVID-19 pandemic, recent results of the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) show. Cleveland had the worst reading score declines in the country on that test known as the “nation’s report card.”

“The drops were more severe than I think I had anticipated,” said Holly Trifiro, education advisor for Cleveland Mayor Justin Bibb. “It’s startling to see how far behind our kids are. It’s the kind of thing that could be keeping lots of us up at night.”

Though concerning,the NAEP don’t appear to have changed recovery plans in a city where students have long lagged behind their more affluent peers and where educators saw the impact of the pandemic unfold daily.

Instead, Cleveland officials are banking on support programs, like the afterschool sessions at Mary Martin which was in place before the pandemic. The recovery strategy also relies on initiatives yet to be rolled out. Some programs, like the district’s summer school initiative, may help, but aren’t drawing all the students that need it.

Cleveland still beat Detroit — the city it routinely trades places with as the poorest district in the country — on the NAEP tests. But Cleveland slipped behind other poor urban areas it often compares itself to, as the pandemic undid more than 15 years of gains on the tests.

Of 26 cities measured, Cleveland had the biggest score drop nationally in both fourth and eighth grade reading assessments. Cleveland’s fourth grade reading scores fell more than five times as much as they did nationally since the last pre-pandemic tests in 2019.

In math, eighth grade scores fell about the national average, but fourth graders tied for the worst drop in the country.

District officials say the results provide a new post-pandemic baseline to measure future improvements from.

“While it’s difficult to see, it (NAEP) does give us the chance to really work on what’s happening,” said school board member Denise Link. She and other board members credited the district for not skipping the tests earlier this year, even when they likely knew the results would be bad.

Whether those scores become a rallying point for any new efforts remains to be seen. Some downplay the severity of the results because of Covid outbreaks and how early tests were given in the school year.

The district is also relying on key programs that other cities are just now turning to in recovery efforts – like the afterschool sessions and accompanying wraparound services – that were already in place or rolling out as the pandemic hit. And a few new efforts, like book giveaways and online tutoring, were already lined up to launch when NAEP results came out.

The district is also in the middle of a leadership switch. Along with having a new mayor this year, district CEO Eric Gordon is stepping down at the end of the year. The school board is in its early stages of its search for a replacement.

The score drop comes as no surprise for a few reasons. Cleveland has long been one of the poorest cities in the nation and multiple analyses show poor students faring worse during the pandemic than more affluent ones.

The district was the least-connected city in the nation, according to 2019 Census data, which put Cleveland behind others in online learning when school buildings closed.

“People didn’t have any access,” said Sajit Zaccharia, a Vice Provost at Cleveland State University and former dean of its education school, who also sits on a district oversight board. said. “You had stories of people trying to get on their phones, trying to be next to libraries with free WiFi, and things like that to try and get access. But only a small percentage of the population could probably even do that.”

Cleveland Teachers Union President Shari Obrenski said acclimating students to school after more than a year away dominated the early part of the 2021-22 school year, leaving little time to catch up by January’s NAEP tests.

“That you saw dips in math and reading on NAEP after students not being at in-person school should be no surprise to anyone,” Obrenski said. “There were people not used to being around other people, students who are not used to being at school all day every day. It was really difficult.”

She’s not convinced that transition is over, even today.

“I don’t know that we’re there yet,” she said. “I think we’re getting there.”

Gordon and others say the Omicron variant of Covid hitting Cleveland earlier and harder than most cities also hurt scores. Right before Christmas 2021, the Cleveland area had the fourth highest Covid infection rate in the country. That forced a week of remote classes just before NAEP tests.

A few programs are key in that recovery. With students disengaged from school and the district having severe chronic absenteeism issues, Gordon added more music, art and gym classes at each school this year. The district also launched an optional summer learning program for both 2021 and 2022.

And the district is counting on Say Yes to Education, a college scholarship and student support program launched in early 2019, to provide much of the boost students need.

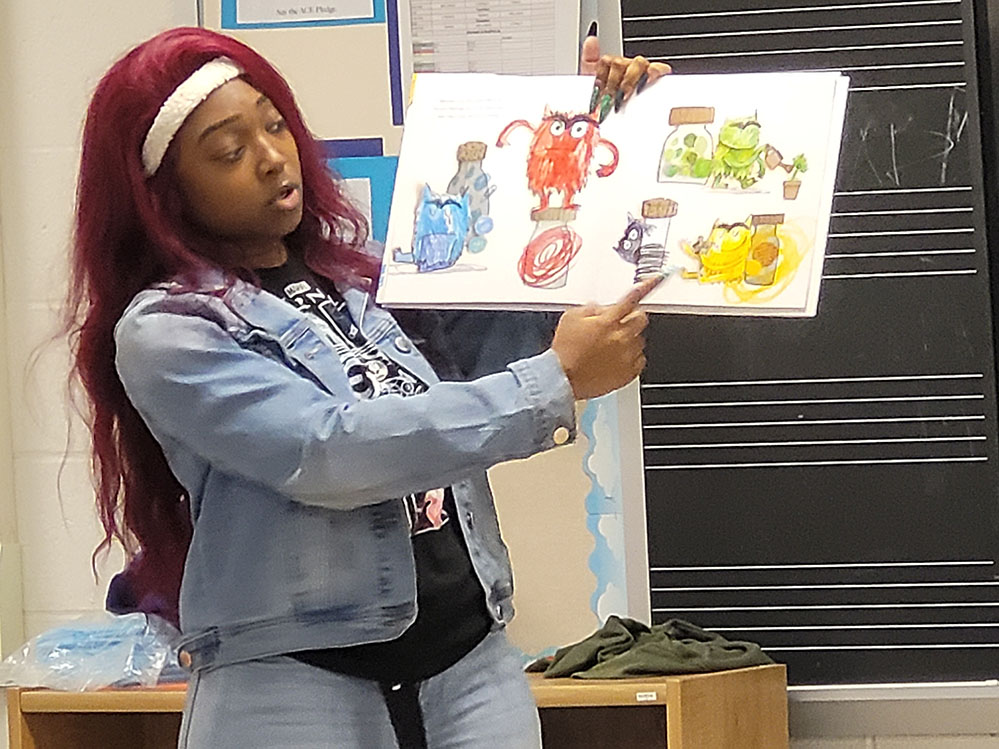

Along with scholarships, Say Yes puts staff in every school to offer supports and afterschool tutoring.

Mary Martin principal Gary McPherson, said afterschool programs, once aimed at helping kids catch up to suburban peers, are now focusing on pandemic recovery.

The district is about to launch an online tutoring program students can access at night for extra help. District teachers will be paid to provide the tutoring each evening with additional hours provided by a private company.

Bibb also plans to launch a still-developing citywide literacy program in December, starting with giving away 50,000 books.

But the programs still aren’t reaching the majority of students. In 2021, the summer program enrolled more than 8,000 participants, a little over 20 percent of Cleveland’s total enrollment. That fell to about 6,500 in 2022.

Afterschool programs also don’t have openings or enough buses.

“You have to start somewhere,” Zaccharia said. “Are there subgroups that are not taking advantage? I think that would be the next stage.”What are strategies that we can use to then try and reach those groups that haven’t taken advantage?”

Help fund stories like this. Donate now!

;)