Women Who Fought for Title IX 50 Years Ago Divided Over Transgender Inclusion

But those who battled for gender equity in school sports in the 1970’s say the current controversy echoes their own struggles

By Alina Tugend | June 15, 2022Margaret Dunkle remembers how complicated it was back in 1975 when she helped draft regulations to curb generations of inequality in men’s and women’s sports.

It was three years after Title IX — the federal civil rights law banning sex discrimination in education — was signed into law. “The issues we are discussing here were the same ones people, including me, were grappling with when the original Title IX regulations regarding single-sex teams were being written,” she said.

The latest debate, about whether Title IX should codify transgender rights — something that could happen when revised regulations are released in the coming weeks — has caused deep divisions, and in some cases, pitted natural allies against each other.

But while the issue is difficult, especially in sports, it’s a mistake to think that things were less complicated when President Richard Nixon signed Title IX into law 50 years ago on June 23, 1972.

“Looking back, things always seem simpler, but I remember how fraught the arguments were, and how difficult it was for people to reconsider their beliefs about boys and girls,” said Susan Bailey, who helped implement Title IX while working at the Connecticut Department of Education. The transgender question “is very polarizing, and people once again want a single, simple solution.”

‘Title IX shook all that up’

The fact that it took three years from the time the law was passed to draw up regulations showed that “the Nixon administration did not have the slightest interest in enforcing this law or equality for women and girls,” said Holly Knox, who was a legislative aide in the then-U.S. Office of Education, covering Congressional hearings on sex discrimination. After the law passed, she became disillusioned with government education and enforcement efforts and established the Project on Equal Education Rights at the National Organization of Women’s Legal Defense and Education Fund.

Although most of the high-profile disputes involving Title IX — which applies to education programs and activities that receive federal funds — now involve sports or sexual harassment and assault cases, the original impetus was much broader.

Employment of women teachers and coaches, pregnancy discrimination and admissions to graduate schools, including law and medicine,were all major issues, said Jean Peelen, who was part of the group drafting the final policy for intercollegiate athletics in 1979.

To demonstrate the law’s impact on graduate admissions, Peelen noted that in 1974, two women were admitted to the University of Alabama’s law school. In 1975, when she entered, 25 percent were women, increasing to 50 percent in 1976.

In elementary and secondary schools, the legislation affected issues from class assignments to textbooks. As just one example, many K-12 schools scheduled advanced math and advanced English at the same time, so boys were steered toward math and girls toward English. “Title IX shook all that up,” said Bailey, who became a professor of Women’s & Gender Studies and Education at Wellesley College.

One of the most complex questions at the time was what could remain single-sex and what couldn’t, from choirs to gym classes to colleges. In that sense, the transgender debate is “a second-generation issue,” said Dunkle, who worked with both the Association of American Colleges’ Project on the Status and Education of Women and the National Coalition for Women and Girls in Education.

While the latest round of Title IX revisions includes important issues for transgender students beyond athletics, one of the major sticking points is whether allowing trans women to compete on women’s teams discriminates against athletes identified as female at birth.

The arguments and solutions proffered today echo many of those Dunkle grappled with in a 1974 paper she authored: “What Constitutes Equality for Women in Sport?”

The paper discusses both competitive and non-competitive college sports and highlights discrimination that was almost universal. Examples included one college that didn’t allow women to use a handball court unless a man signed up for her and a large midwestern university that reserved two hours of pool time for “faculty, administrative staff and male students.” There was no reserved time for female students.

Then it tackled how sports teams should be configured, the very issue at the core of the current debate. Dunkle laid out the options: Should competitive sports teams in college be co-educational? Single sex? A women’s, men’s and mixed-sex team? Should teams be based on height and weight? Should top women athletes should be able to apply for a position on the men’s team? While this might allow elite female athletes stronger competition, critics argued it would be administratively unwieldy and result in skimming the best athletes off women’s teams.

“It is almost painful to read the old paper,” Dunkle said. “There were all these choices and all were imperfect.”

Ultimately, a kind of “separate but equal” option won out for most competitive teams. Of course, decades later there are many examples of women athletes treated as second-class citizens, but the idea of girls and women playing separately from boys and men on most competitive teams has become the norm.

Backlash to Lia Thomas’s victory

The sheer numbers tell the story of Title IX’s success: Before the law’s passage, there were 300,000 girls and women playing high school and college sports nationwide. Today, there are more than 3 million.

But the transgender issue has unsettled what once seemed resolved. University of Pennsylvania swimmer Lia Thomas heightened the debate after placing first in the 500-yard freestyle event in March. She became the first openly transgender woman to win an NCAA Division I national championship, but as a man, ranked 65th in the event.

The emergence of the issue as culture war fodder, particularly among Republicans, makes it all the more uncomfortable for those who have fought for women’s equality and back transgender rights in employment, housing and education.

Eighteen states have already passed bills prohibiting trans girls from competing on girls high school sports teams. Most recently, the Ohio House of Representatives passed a bill called “The Save Women’s Sports Act” that bans anyone not identified as female at birth from participating in women’s sports in high school and college. If an athlete’s sex is questioned, she would be required to produce a doctor’s note that includes an examination of her “internal and external reproductive anatomy.” The Senate has not yet voted on it.

The American Civil Liberties Union has taken a stand unequivocally supporting the right of trans women to play on women’s teams, and the International Olympic Committee last November issued a framework that states athletes should not be excluded solely on the basis of their transgender identity or sex variation.

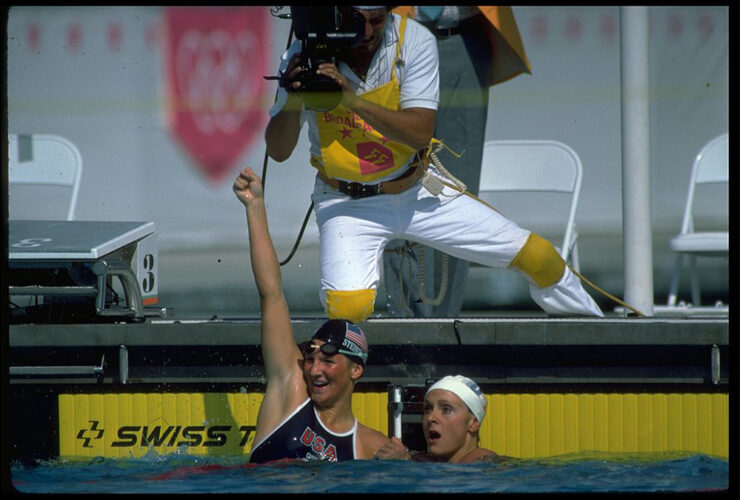

But Nancy Hogshead-Makar, who won three gold and one silver medal for swimming in the 1984 Olympics, argued that allowing trans women to play on women’s sports teams means most women will lose out — which, she said, goes against everything Title IX stands for.

For Hogshead-Makar, it all comes down to biology. Science, she said, has shown that transgender women — in particular those who have gone through male puberty — will almost always have a substantial physical advantage.

“Equality requires separation,” said Hogshead-Makar, now a lawyer who runs Champion Women, an organization aimed at supporting women and girls in sports and educating about Title IX. In 2020, Sports Illustrated listed her as one of most influential and powerful women in sports. Understanding of the biological differences in trans women is evolving, but recent research shows that there may be residual muscle mass and strength advantages even a year after testosterone suppression.

Hogshead-Makar swam competitively at a time when trainers and coaches gave elite East German athletes steroids disguised as vitamins. The scandal was exposed after the Berlin Wall came down in 1989.

“They were doped to the gills and everybody knew it,” she said. “And it felt like nobody cared about us. We were expected to be feminine, gracious losers.” She was victorious in the 1984 Olympics, she said, only because the Soviets and much of eastern Europe didn’t compete. The U.S. had boycotted the 1980 Olympics in Moscow to protest the Russian invasion of Afghanistan; four years later, the Soviet Union and its allies said they would not attend the Los Angeles-based Olympics because its competitors would not be safe amid anti-Russian hysteria.

‘I’ve come to the conclusion it’s not ok’

The move to allow trans girls and women to compete on female teams leaves her and many other women athletes feeling the same way they felt during the doping scandals, she said — forsaken and undefended.

Donna Lopiano, an all-American softball player who heads a sports consulting company, said one option will not fit all trans women. It depends on when they went through puberty, if they received hormone therapy and what sport they’re playing.

She suggested multiple choices need to be considered, some of which mirror those considered by Dunkle in 1974. Should there be men’s and women’s teams, and a third class open to everyone, including transgender athletes? Should inclusion depend on the sport and whether it requires strength or speed? Should there be handicaps like in golf? Separate scoring?

“We’ve gone through this with athletes with disabilities,” she said. “Fair competition has to outweigh social justice if the idea is identical head-to-head competition.”

Peelen and Knox, both of whom are quick to acknowledge they have no special expertise in transgender issues, have landed on different sides of the question. Peelen said she first agreed that trans girls and women shouldn’t play on female teams.

But once she realized how small the number of such athletes are — estimated at less than 1 percent of the population — she changed her mind.

“In any high school, you could have a girl 14 or 15 years old who is six feet tall, and they let her play,” she said. “If the fear is that trans women are going to take over because they are faster or stronger, that’s true with anyone who doesn’t fit in with the norms.”

She initially contemplated what rules could be applied to even things out, such as factoring in weight and height, but decided, “This is absurd. Why not just recognize for some very small group of people on a sports team in a high school or a college somewhere in the U.S., it could seem unfair?”

Utah Gov. Spencer Cox, in vetoing a bill that banned transgender athletes from playing in girls’ sports, was moved by the same reasoning: Of 750,000 students playing high-school sports in Utah, only four were trangender, and just one played for a girls’ team. He also cited research showing that feelings of belonging can reduce the risk of suicide among transgender teens.

The legislature overrode his veto.

The numbers of trans athletes could increase as the transgender population as a whole grows. While still a very small minority, the trans population has doubled in recent years. The Centers for Disease Control recently reported that 1.4 percent of 13 to 17-year-olds identify as transgender and 1.3 percent of 18 to 24-year-olds do so.

Knox ultimately took the opposite path from Peelen, first believing trans women should be allowed to compete on girls and women’s teams, then reconsidering after learning more about the science.

“I’m delighted Title IX protects LGBTQ people from discrimination in admissions, employment and other areas, but because there are distinct biological differences, it would be unfair to let those who are born male and transitioned after puberty compete against biological women in competitive sports,” Knox said. “I’ve come to the conclusion it’s not ok.”

Dunkle is still figuring it out. She supports including transgender students in almost all areas but doesn’t see how it could work in athletics without disadvantaging those identified as female from birth. Speaking from experience, she said, “Any policy that they come up with is going to be imperfect. You have to look at the results and effects, not just what looks fair in theory.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter