5 Takeaways from Historic 10-Week Columbia University Student Workers’ Strike

Help fund stories like this. Donate now!

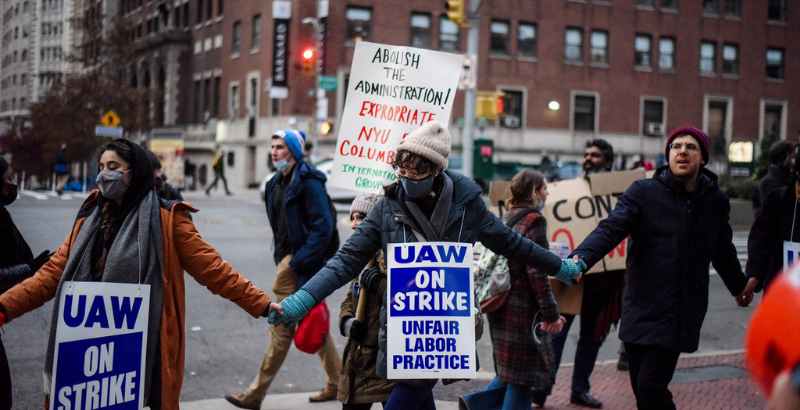

The largest labor strike in the country, the longest higher education has seen in a decade, ended Friday.

After 10 weeks, nearly 3,000 undergraduates, researchers, instructors and graduate teaching assistants at Columbia University celebrated higher wages, expanded child and dental care, and greater protections against harassment and discrimination.

Over the past year, relationships between student workers and administrators became increasingly frayed at Columbia, one of the country’s wealthiest private universities with a $14 billion endowment. Many of the workers described living paycheck to paycheck, securing food stamps and public benefits to survive, with some earning just $15 an hour.

“We are thrilled to reach an agreement with Columbia after seven years of building toward this first contract. What our members achieved is impressive, but this is only the start,” Nadeem Mansour, bargaining committee member and PhD candidate, said in the Student Workers of Columbia union statement.

From Nov. 3 to Jan. 7, the 3,000-member SWU, a United Auto Workers Local 2110 union, protested with support from faculty and continued striking amid perceived retaliation from administrators.

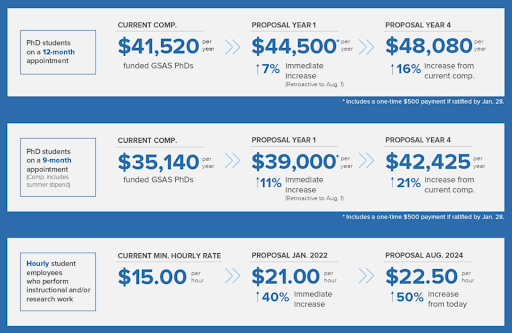

The newly proposed four-year contract significantly expands working protections, including:

- Pay raises ranging 6 to 9 percent for PhD students;

- Increased minimum wage for hourly research and instructional workers from $15 to $21 effective this January and $22.50 by August 2024

- $5,000 stipends for child care, to increase $500 annually

- Access to an emergency health fund of at least $300,000

- Coverage for 75% of dental premiums

- The right to outside, third-party abitration in the event of discrimination or harrassment claims

SWU members will vote to approve or reject the contract late this month, with a decision expected by Jan. 28.

But passage is not certain.

Union members are prepared to reject the contract if the University does not compensate for completing fall semester teaching responsibilities. Without the “back pay,” hundreds of undergraduates would also go without feedback and final grades in graduate-run classes.

The strike marked SWU’s second in less than a year. Previous efforts to solidify better working conditions came to a halt last spring, when members rejected the University’s proposed contract.

Below, we’ve compiled five facts to remember from the last few months of higher education labor organizing:

1. The strike solidified the role and strength of student unions in higher ed.

Though higher education institutions have relied on student labor for centuries, Columbia’s contract would become one of the first 10 to exist at private American universities.

It would also be the first to recognize all undergraduate teaching and course assistants.

The union’s fight resonated well beyond the walls of higher education. New York comptroller urged university President Lee Bollinger to prioritize negotiations and finalize a “fair contract” in late December, for the “greater good of New York City.”

U.S. congress members Mark Takano (D-CA), Jamaal Bowman (D-NY) and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY) also expressed support for striking workers.

2. Threatening emails from University admin only fueled support.

In early December, an email from the University’s human resources department stated, “Please note that striking student officers who return to work after December 10, 2021, will be appointed/assigned to suitable positions if available.”

The likely scare tactic appeared to have the opposite effect. Immediately following, hundreds showed up in protest on Columbia’s central campus, blocking entrances.

Some say the email galvanized more faculty to support the union’s plight, with roughly 100 joining in protest on Dec. 8.

“That’s part of what I think is driving more faculty to come out. It was retaliatory, it was inappropriate and it was hugely disturbing,” Susan Witte, a professor at the School of Social Work, told Ashley Wong of the New York Times.

3. Many question the legality of Columbia withholding doctoral stipends, not just salary wages, during the strike.

Doctoral students are missing roughly $8,000 — separate from teaching salaries withheld from striking — from the fall semester. The money can make or break students’ ability to pay rent, food and living essentials.

When the union voted to strike, members were under the impression that the stipends would be guaranteed given they compensate students for scholarship, not labor.

Many await word from the University, falling further into debt and possibly forced to disenroll because of the financial stress.

4. Students on strike relied on mutual aid for rent, food, child care and healthcare costs.

“SWC members are thousands of dollars in debt from the strike and need immediate support to pay late fees, rent, and bills,” reads SWU’s Twitter, soliciting support for their hardship fund.

The mutual aid fund has raised $378,392 to date, yet split among 3,000 union members, would only make a dent in a week’s worth of food.

PhD candidates’ compensation packages were also up to $18,000 below a living wage before striking. And strike funds, made accessible through United Auto Workers, were capped at $275 weekly.

The financial strain has driven “back pay” and stipend reimbursement to the forefront of debate as the union enters its discussion period before the end-January vote.

5. This marks the end of the largest strike in the U.S. and longest higher education strike in more than a decade.

Fed up with poor wages, costly healthcare amid a pandemic, increasing tuition, mounting student debt amid a host of other woes, students organized en masse in 2021. A swell of strikes and renegotiated contracts made headlines, most notably at New York University and Harvard.

Yet the sheer length of Columbia’s strike — 65 days, which found students gathered in freezing picket lines — sets it apart from past education labor actions.

“There is no doubt that this has been a challenging period for the University, yet all who were involved in collective bargaining shared the common goal of creating a stronger Columbia…” Provost Mary Boyce said in a statement.

Help fund stories like this. Donate now!

;)